One of the great joys of the pursuit of Hi-Fi is just that: the pursuit. In the course of finding the best we find many substitutes, these being speakers and electronics which please us in various ways, or offer small glimpses of better. But best? Never. It isn’t possible to have the best, only whatever best suits your tastes at any particular moment. Right? So where does the Acora QRC-1 fit in with that conversation?

Anything that achieves that elusive b-word quality would mean that the pursuit would be over, and this is sort of the question at the heart of my experience with Acora Acoustic’s QRC-1 loudspeaker. I’m not yet implying that the Acora QRC-1 is the best speaker I’ve ever heard — you’ll have to wait for the conclusion for that particular puzzle to get unraveled. What they do however, redefines the question of the pursuit.

Words and Photography by Grover Neville

So now we have our characters, the pursuit and the best. The pursuit is our heroic protagonist, balancing many things, depending on who you ask. Transparency, detail, dynamics, tonal color or lack thereof, transient fidelity, accuracy of the phantom image, frequency response, and all of those wonderful qualities we search for in various amounts. And the best is our metaphorical sermon on the mount, Nirvana, burning bush if you will — incidentally, fun fact, I just learned today there is actually a bush in the middle east which will spontaneously combust without burning its leaves. Fascinating stuff.

Acora QRC-1

Our goal in the pursuit is always to achieve the best, but we are waylaid by the characteristics any given speaker or amplifier possess – this one is dynamic, but not as flat, whereas this other one is flat but not as dynamic. What to do? The answer is often to swim further upstream. When the Acora QRC-1 speakers first arrived at my house, I had an epiphany about this dichotomy, and it arrived from a most unexpected source.

Classical music and I have a rather complex history — we are at once old friends, but studying classical music in a rigorous conservatory environment sort of breaks your brain. Add on to this a healthy dose of classical engineering and you have a recipe for that greatest enemy of the pursuit: pickiness. I am incurably picky about classical recordings, in the way many of us are picky about audio equipment. This recording has a great tempo, but the dynamics are poor. This recording has a great tone, but the intonation is poor. And the list goes on.

Compounding all of this difficulty is the simple fact that the vast majority of hi-fi audio systems are completely incapable of reproducing classical music in a manner resembling transparent, not to mention enjoyable. It is the equivalent of the magician performing the sleight of hand a fraction too slowly, and allowing the edge of the hidden card to show. Even a miniscule peek shatters the entire illusion.

What mostly causes this is the way classical music is recorded: even chamber music is recorded mostly using small diaphragm condensers and omnidirectional patterns in often excellent acoustic spaces with minimal digital limiting or destruction of the delicate high frequency information that results from such acoustics. This is music which often sounds pure, clean and free of artifacts.

Classical music on many hifi systems is a triptych of bizarre colorations. That slight forwardness in the midrange that sounds so appealing with popular music or rock, functions to make strings and winds honky and harsh, narrow-band bass boosts that give mainstream recordings a little extra bounce simply obscure the intricate string bass and piano lines in chamber and orchestral recordings, and that delicate high end I mentioned often crumbles apart even on systems with only a small degree of high-frequency stylization. Classical music, and by extension other forms of Chronically Extremely Acoustic Music™ — bluegrass, experimental, some jazz and world music — demand dynamics, frequency linearity and purity of tone. Like spoilt children, hungry hippos and stock traders, they must have it all.

The Sound: Acora ARC-1

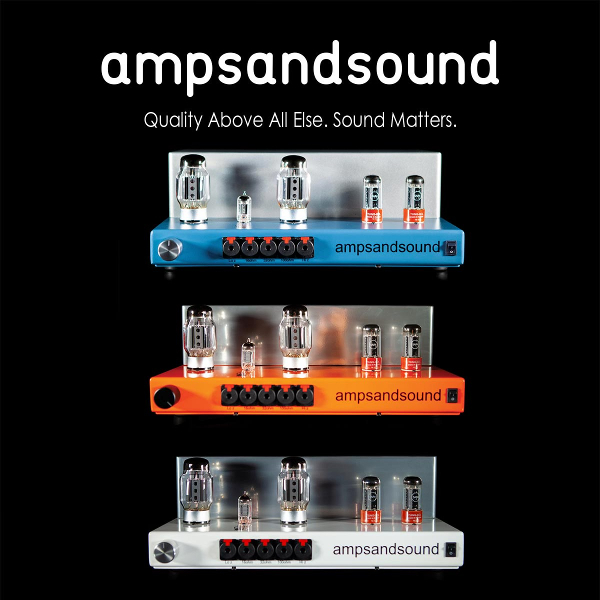

What the Acora QRC-1 does, is dispense with this approach entirely. On firing these up for the very first time, leashed to an ampsandsound Black Pearl which warrants its own story, my assumptions had a wrench thrown in them. Now, if you know me, you know I’m well informed on the entire Acora line. Valerio Cora was generous enough to treat me to a direct A/B of all his speakers last year at Acora HQ in Toronto, including the upcoming VRC. I know how these speakers sound. Or so I thought.

Chronically Extremely Acoustic Music™ doesn’t send me scrambling for my iphone, airpods or any system low resolution enough to fool me into focusing exclusively on the performance. It simply sounds like… well like it’s supposed to.

Ok, so let’s qualify that. There are no tricks that can really accomplish this, and in experience recording classical and acoustic music, my observation was generally because this kind of music relies less on processing for its core sounds. Sure, we use EQ, editing, delay lines for phase correction and even some compression. However, unlike popular and more heavily electronic processes, the goal with classical and acoustic music is to capture the sound of a self-balanced ensemble in a live acoustic, relatively as transparently as possible. It is the photograph versus the digital painting.

Let’s circle back to the high frequency though. Most of the typical western instruments don’t have fundamentals above the 4-6 kHz range except for a few specialized wind instruments or extended techniques. What is lacking in fundamentals however, is made up for in harmonics, which are dense and rich in this genre, and also the enormous amount of ambient information that is often captured by the highly detailed omnidirectional microphones frequently used, and you have a recipe for something that resembles a dynamic bed of noise much more than any popular production.

The Acora QRC-1 elegantly navigates this problem not by achieving the absolute flattest frequency response at all costs however. Oftentimes if a driver and cabinet combination cannot reproduce a frequency, the designer will solve the problem electrically in the crossover, or occasionally mechanically by applying more damping. This has the effect of allowing you more control over the frequency response, but frequency response is only as good as the intended listening level.

My essential theory here is that a driver able to maintain a smooth frequency response with broad Q factor at many levels, and good dynamics, will tend to sound perceptually flatter than a driver which measures perfectly flat only at a single reference level with a sine wave. After all, music is a dynamic signal and not a sine wave.

Back to the Acora though. The combination of an extremely rigid cabinet and absence of excess electrical or mechanical damping beyond what is necessary gives these speakers an almost electrostatically quick midrange and treble, which neither projects nor presents a soundstage, but from which the ambience of acoustic recordings simply emerges as if from some kind of audio ether.

If that seems like a slightly metaphysical take, it is. Along the journey of the pursuit, I have encountered enough compromises that I felt that the best was only the most preferable collection of compromises. In place of that idea the QRC-1 has come along and shown me that if we are talking sheer transparency, and fidelity to the source, as we desire in Chronically Extremely Acoustic Music™ then this is indeed The Best. But how does it fare with other material?

To answer this question I have to place the QRC-1 in the Acora lineup a little more accurately. Having compared the lineup, the SRC-1 and QRC-1 occupy an interesting position. Though they both use a similar woofer as the SRC-2, the tweeter used in both SRC-1 and QRC-1 completes the sole appearance of a soft dome in the entire product line. Both the SRB and SRC-2 utilize a Beryllium tweeter option. While the Beryllium is a little sharper, a little more defined and yes a hair more detailed, the soft dome I think will appeal to many as an exceptionally linear and slightly more pleasing option. It asks just a little less of partnering electronics, and for my tastes, which tends towards paper drivers and soft breakup modes, it has a tendency to be tolerable a few notches higher into the “loud” zone of any amps volume range. I find it also a little smoother in response than the Beryllium, and just a hint more coherent.

Our INDULGR Audiophile playlist includes 600+ tracks perfect for auditioning high-end audio gear, and was curated by our team of editors.

The absence of a second woofer, a la the SRC-2, also means that given an appropriate size space, the QRC-1 will be perceptually more linear. Now, the second driver of the SRC-2 is meant to fill a larger space, and so it does have a little more output which will result in linearity at further distances and in a bigger space. The proverbial bigger gun. But for many living spaces — mine is a relatively modest sized but lofted room opening up to 1,500 square feet — the QRC-1 provides more umph than most will ever need.

The coherence and liquid smoothness of presentation combine with the true-to-source nature of Acora speakers at large for an experience which is probably my favorite of the entire lineup. The softer breakup modes of the soft dome tweeter, and the slightly softer sound of the quartz enclosure versus the absolute precision of the SRC/B granite, gives an effortlessness of presentation to the QRC-1 that is addicting to me for acoustic recordings.

None of this is to say the QRC-1 does not handle other genres deftly either, and of course it retains the trademark vanishing-act transparency of other Acora speakers, with seemingly endless bandwidth and soundstage width, lightning speed low end, and a total absence of audible cabinet coloration. It was simply with acoustic music where I noticed this most — everything I played sounded so good it almost hurt.

The Conclusion: Acora QRC-1

The Conclusion: Acora QRC-1

I rarely mention recordings, but I’ll make an exception: the Sistine Chapel Choir Veni Domine album, or really any of their recordings, were a goosebump inducing experience on the QRC-1s. Something about the acoustic ambience of this space is just electric, and on quiet, high resolution systems, it is an extremely special experience. I could listen to recordings of noise made in that space all day long, it’s just that good.

Apart from sound, I’ll let the photographs speak for themselves. While I’ve certainly never been bothered by the granite cabinets of Acora speakers, the quartzite cabinetry of the QRC-1 in a matte, grainless white was especially striking. In my living room alongside an almost all-white electronics stack consisting of ampsandsound and Meitner, the effect was akin to walking into the MoMA. Objet d’Arte, the QRC-1 in white cut an angular, monolithic figure, yet unlike many white wooden box speakers, have none of the chintzy knock-off Italian mother-in-law looks many have come to associate with white hi-fi. These are avantgarde, post-Bauhaus, Warhol white. Me likey.

I’ve spilled more words on this speaker than I have on a piece of audio gear in a long time, and suffice to say, the QRC-1 have firmly pegged the pursuit in my household. Are they the best? Well, they’re the best I’ve heard for those seeking to end the pursuit of hi-fi with a speaker which tells the auditory truth in all things, or as close as we can get. I can’t think of a speaker which combines this level of transparency, speed, dynamism, and utter lack of coloration in a single package at this price point. Unless of course, you’re looking to buy another Acora…

About the Author

Wanderer, Wonderer, Musician, Actor

Grover Neville resides in sunny Los Angeles, California, and is a graduate of the Oberlin Conservatory of Music where he studied music and creative writing. After graduating he pursued a freelance career in audio, and professional research in the fields of Auditory Cognition, Psychoacoustics, and Experimental Hydrophone Design. He is a native of Chicago, Illinois and previously did work there as a mixing and mastering engineer, working in music genres such as Avant-garde Classical and Jazz.

As a transplant to Los Angeles, Grover still works in the music industry, but now adds the video game and film industries to his calling. He is actively pursuing a career as an independent musician, composer, and producer.

Grover previously contributed to Innerfidelity, Audiostream, and Part-Time Audiophile—before becoming an editor and co-founder of INDULGR magazine.